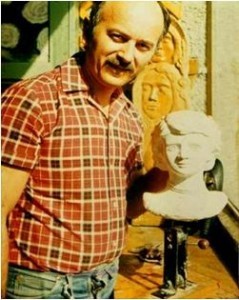

Liviu Corneliu Babes Photo: Web

Liviu Corneliu Babes Photo: Web

The dark pages of history have recorded the selfless sacrifice of millions of faceless and often nameless heroes buried in native and foreign lands, quickly forgotten by the collective memory of their brethren whom they protected and saved so that they can have a better life, a brighter tomorrow, a happier future.

Occasionally the hero has a name; he/she commits such a solitary act of bravery and courage that it defies description. But the ultimate self-sacrifice sometimes is quickly forgotten or even scorned.

In 1969 Czechoslovakia, Jan Palack, a 21 year-old student set himself on fire on the steps of the National Museum in Prague in order to protest the USSR military intervention in his country.

Jerzy Popieluszko, a Catholic priest who sympathized with the labor group “Solidarnosti,” was assassinated in October 1984 by the Polish police.

Chris Gueffroy of the German Democratic Republic, a communist satellite state of the Soviet Union, was killed while trying to climb the Berlin Wall in order to flee from communism. Nobody ever tries to flee from capitalism. He was literally the last straw in the west’s desire and campaign to demolish the Wall of Shame built by East German communists in 1961.

The future president of Czechoslovakia, the writer Vaclav Havel, was sentenced to nine months in prison in February 1989, a victim of his anti-communist thoughts, ideas, and writings.

Author Mircea Brenciu dedicated his book, “The Martyr,” to a hero who may have changed the course of history with his act of defiance and bravery. His self-sacrifice on March 2, 1989 in Poiana Brasov, Romania, helped initiate the end of 24 years of Ceausescu’s brutal communist dictatorship. Yet he is largely unknown today to his own people and to the West.

Mircea Brenciu asked rhetorically in his book dedicated to the most incredible brave man, Liviu Corneliu Babeş, “Why don’t Romanians love their authentic heroes?”

It is understandable why that was the case prior to the “fall” of communism. “Securitatea [security police] had ears everywhere, even when you were quiet, you were a suspect.” Unfortunately, “many of the torturers of yesterday and their replacements can be found today in key political, social, cultural and especially financial positions,” added Brenciu. It is clear why there is so little mention of the most tragic Romanian martyr.

Christianity in general considers suicide unholy and many priests refuse to bury such deceased in holy ground. Only God can give the right to life and only God can take it away.

The Orthodox Church considers suicide an act of cowardice, not of heroism. According to the young priest I spoke to on my trip to Poiana Brasov in 2015 to pay my respects to a Romanian hero, Babeş is an apostate and not worthy of praise.

A small monument is located a few feet from a small wooden church in the meadow where Babeş sacrificed himself to bring attention to the rest of the world to the plight of the desperate Romanian citizens living under the boot of communism.

There is a street that bears his name in Brasov, there is a metal cross on the bottom of the ski slope where the end of the tragedy unfolded, the type reserved for road accidents, and a modest monument in Poiana Brasov with the bronze effigy of the martyr created by the artist George Jipa.

Liviu Corneliu Babeş (1942-1989) made the ultimate sacrifice on March 2, 1989, several months before the December revolution that toppled the brutal communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena. On a very crowded ski slope in Poiana Brasov where skiers from the West were vacationing, Babeş chose to set himself on fire, protesting the atrocities committed by the Ceausescu regime.

Brenciu wrote how, in a cathedral stillness, the crowd witnessed in shock and horror the unimaginable act of a skier on fire, gaining speed, not making a sound, as the smell of burnt flesh filled the air. At the bottom of the slope, Babeş fell, his body licked by the flames fed by oxygen and the clothes soaked with gasoline. From underneath his smoldering clothes, he pulled out a sign that read, “STOP MURDER! AUSCHWITZ=BRASOV.”

Brenciu described how two tourists from Scotland, who happened to be very close to where the skier collapsed, covered his smoldering body with coats, in an attempt to put out the flames. Douglas Wallace was subsequently interviewed by the Sunday Times on March 12, 1989. (Burnt Alive: the Suicide that Shamed Romania)

When the ambulance arrived, Babeş was still alive, the barely audible labored and pained breaths the only witness to his intense pain and suffering. According to Brenciu, the stretcher carriers, dressed in white but with police uniforms underneath, and with menacing looks, shooed the crowd away. They were not there to help the immense suffering of the dying Babeş; they were there to cover up the incident. They announced loudly to the crowd that this man was mentally ill and there was nothing to see. Perhaps the crowd would have believed him, had it not been for the yellowed paper sign Babes carried with him that spoke clearly why he immolated himself. “One of the residents of the concentration camp called Romania broke the silence, but the price was his personal sacrifice,” said Brenciu.

Nobody knows the last indignities this dying hero had to suffer while in custody of the so-called “saviors.” The Romanian word for ambulance is “salvare,” [salvation]. Their mission was quite different, to get to the bottom of his sacrificial act that dared to destroy the harmony of Poiana Brasov, of the fake reality created for foreign tourists that aimed to give them the false impression that Romanians lived in excellent conditions in Ceausescu’s “most humane and wise political regime possible.”

Mircea Sevaciuc explained that Liviu Cornel Babeş “was buried by communists and Securitate.” After the revolt in November 15, 1987, Liviu was never left alone. He had sent a letter to Free Europe, asking for a better life for all Romanians. Since that time, a friend said, “He was afraid to walk in the streets. One day he told me at work – they want to get me but they won’t succeed because I am going to set myself on fire.”

Babeş’s widow, Etelka, and their daughter, were not left in peace to mourn the loss of their beloved husband and father. Her apartment, located in one of the drab concrete apartment high-rises, was constantly watched by the Security Police. They came and searched everything and confiscated any notes and sketches he may have left behind. An amateur painter and sculptor, he had a small collection.

One day a friend accompanied Etelka to the cemetery where Babeş was buried. They were followed by a Security Police officer who did not bother to disguise his obvious spying. Even in death, the communist police state did not leave her Cornel alone because he had the courage to sacrifice his life in such a public way in order to expose communism and its paid torturers and informers who robbed the masses of their humanity and freedom under the false pretense of “social justice” and equality.

I appreciate your article that teachers are born, not made. We taught children to read using mothers with just a basic education, and a love for children. We gave them one week of training. Our children excelled.

Thank you, Jim Hollingsworth. Keep up the good work!