Driving through the winding roads of the Cumberland Valley, Pennsylvania felt like riding a roller-coaster sixty miles an hour, with exciting and breathtaking drops. It was a warm February day yet I could only imagine how treacherous it must be when ice and snow cover these roads.

Driving through the winding roads of the Cumberland Valley, Pennsylvania felt like riding a roller-coaster sixty miles an hour, with exciting and breathtaking drops. It was a warm February day yet I could only imagine how treacherous it must be when ice and snow cover these roads.

I admired the picturesque apple orchards dotting the landscape and stopped to smell the fresh air, the soil, and to hear birds singing. Even in its dormant state, the sunny day, the stillness, the beauty of the fertile trees as far as the eyes could see, was captivating.

We were bound for Carlisle, Pa, the seat of Cumberland County. Carlisle has a population of 19,162 (2016) excluding the students who attend Dickinson College, a liberal arts college focusing on international education and global education.

We were bound for Carlisle, Pa, the seat of Cumberland County. Carlisle has a population of 19,162 (2016) excluding the students who attend Dickinson College, a liberal arts college focusing on international education and global education.

Carlisle Barracks is one of the oldest U.S. Army installations and the most senior military educational institutions in the United States Army. The U. S. Army War College is also located on the grounds of Carlisle Barracks.

Cumberland County was crossed by major roads and had an important role in the westward migration. It is interesting to note that the historic district is constantly crossed and clogged by eighteen-wheeler trucks.

The settlement of Carlisle was planned in 1751 by John Armstrong Sr. Immigrants from Scotland and Ireland settled in Carlisle and farmed the Cumberland Valley. They named it after Carlisle, Cumberland, England, and even built the former jail house in the shape of The Citadel in the English city. This jail is now used as general government offices.

The settlement of Carlisle was planned in 1751 by John Armstrong Sr. Immigrants from Scotland and Ireland settled in Carlisle and farmed the Cumberland Valley. They named it after Carlisle, Cumberland, England, and even built the former jail house in the shape of The Citadel in the English city. This jail is now used as general government offices.

Carlisle was a munition depot during the American Revolutionary War which was later developed into the U.S. Army War College. The munitions were kept in a barrack built by Hessians in 1777 which is now a museum located on the Carlisle Barracks grounds next to other historical buildings which have been transformed and modernized through time.

Carlisle was a munition depot during the American Revolutionary War which was later developed into the U.S. Army War College. The munitions were kept in a barrack built by Hessians in 1777 which is now a museum located on the Carlisle Barracks grounds next to other historical buildings which have been transformed and modernized through time.

A Revolutionary War legend, Molly Pitcher, who died in Carlisle in 1832, is buried in the Old Public Graveyard. There are signs all over Carlisle, reminding visitors of its tumultuous history. For such a small borough, it has found itself often at the crossroads of American history in the 18th century.

When a march was planned in favor of the United States Constitution in 1787, Anti-Federalists initiated a riot in Carlisle. During the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops assembled in Carlisle under the leadership of President George Washington. The Presbyterian Church in the historic district was the place where President Washington worshipped while in Carlisle.

A local lawyer, Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, founded Carlisle Grammar School in 1773 and established its charter as Dickinson College, “the first new college founded in the newly recognized United States.” One famous alumnus, who graduated in 1809, was the 15th U.S. president, James Buchanan.

Another prominent lawyer and scholar, James Hamilton (1793-1873), left a $2,000 gift and a 60’ X 60’ lot in his will that would be used to construct in 1881 a two-story brick building that became the Hamilton Library Association, dedicated to housing its collection and eventually a research library about Cumberland County.

According to the Historical Society, another signer of the Declaration of Independence, George Ross (1730-1779), was a prosecutor for the British Crown in Carlisle in the 1750s and 1760s. He had been loyal to King Gorge III, but switched over to the Revolutionary movement. He was the last of the Pennsylvania delegation to sign the Declaration of Independence and the uncle of Betsy Ross.

The Dickinson Law School founded in 1834 is the fifth-oldest law school in the U.S. and the oldest law school in Pennsylvania. The locals were quite upset when the law school ended its affiliation with Dickinson College in 1914 and reorganized as an independent institution, later merging into the Pennsylvania State University in 1997 as Penn State Dickinson School of Law.

Carlisle was a stop for the Underground Railroad, leading up to the American Civil War. As part of the Gettysburg campaign, General Fitzhugh Lee, attacked and shelled the town on July 1, 1863. There is a cannonball dent still visible on one of the columns of the historic county courthouse.

Many of the early settlers of Pennsylvania were Scots-Irish who brought with them their Presbyterian faith. By 1730, they were settling in Cumberland Valley, in the fertile land near the Conodoguinet Creek.

The First Presbyterian Church of Carlisle, the oldest public building in Carlisle, was constructed in 1757. Colonists met there in 1774 to declare their independence from England and President Washington worshipped there in 1794.

In an attempt to force Indians to reject tribal culture and adapt to western society, U.S. Army Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt established Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879, a federally-supported school for American Indians off a reservation. The school was closed in 1918 and the property transferred back to the War Department to be used as a military hospital for soldiers wounded during WWI.

The Indian School memorabilia was packed up and employees helped students return home or transfer to other schools. The school’s 39-year history came to a sad end on September 1, 1918. There was no formal job placement in place and society at large did not rush to hire their graduates.

Additionally, those students who chose to go back to their traditional lives were not accepted back with open arms, they were considered having gone “back to the blanket.” According to the Carlisle Archives, “other Native Americans considered them ‘apple Indians,’ red on the outside and white on the inside.” Some graduates became the reservation’s translators and interpreters. The trades they had learned in the western school were often useless on the reservation.

The museum archives describe how Asa Daklugie, an Apache, remembers the ‘civilizing’ process which stripped children of all outward signs of traditional life. “We’d lost our hair and we’d lost our clothes: with the two we’d lost our identities as Indians. Greater punishment could hardly have been devised.”

The archives recall, “One by one, the boys’ long hair was cut, a traumatic experience that caused resistance and deep resentment. Their clothing was replaced with military uniforms for the boys and Victorian dresses for the girls. For many students, who had arrived dressed in their finest garments made by family members, losing their familiar regalia was painful.”

The most famous student was Jim Thorpe (1887-1953), a halfback football hero who led its team to upset victories against the powerhouses Harvard, Army, and University of Pennsylvania in 1911-1912. Thorpe was also an Olympic gold medalist and coach, considered and named in 1950 “the greatest athlete in the world” of the first half of the 20th century.

Ten Cumberland County residents received the Medal of Honor. A Liberty Tree stands in the yard of the Old Courthouse (erected in 1766), honoring the Iranian hostages of October 17, 1980.

On the site that had been chosen for Carlisle, there were five major Indian paths that converged, paths of culture, trade, and war. Cumberland valley was settled by Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands, Susquehannock, Iroquis Confederacy, Lenape, and Shawnee peoples. The Cumberland valley connected Iroquois lands to the Cherokee and Catawba in the Carolinas.

In the 19th century, the Cumberland Valley Railroad opened new ways for goods and people to travel and the speed of life changed. Scientific agriculture was introduced and allowed habitation of legal immigrants who settled in the area. Eventually the railroad system would give way to automobiles, trucking, and to the development of our modern but aging highway system.

Many areas and buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places such as the Carlisle Historic District, Carlisle Indian School, Hessian Powder Magazine, Carlisle Armory, and Old West, Dickinson College.

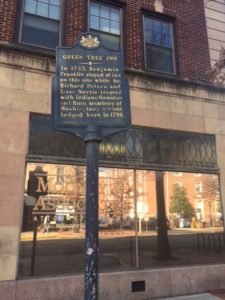

The Green Tree Inn had many distinguished guests, among them Benjamin Franklin in 1753, Hamilton and Knox, members of Washington’s cabinet in 1794.

The Green Tree Inn had many distinguished guests, among them Benjamin Franklin in 1753, Hamilton and Knox, members of Washington’s cabinet in 1794.

James Wilson (1742-1798), born in Scotland, who rose to the rank of Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania State Militia, cast the deciding vote for independence for Pennsylvania, was one of the six original justices on the Supreme Court, and a founding father of Dickinson College. He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and was twice elected to the Continental Congress.

James Smith (1719-1806) was another signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was born in Ireland and studied law at his brother’s office in Pennsylvania.

Another fascinating local was Daniel Drawbaugh, expert mechanic and inventor. He held seventy patents, thirty-five related to the telephone. He invented stone pneumatic drills that were used in the building of the Library of Congress, a coin sorting machine, and a charcoal stamping machine. His Great Cumberland County Clock was an interesting electrical invention that could not keep accurate time because of variations in ground current.

Another fascinating local was Daniel Drawbaugh, expert mechanic and inventor. He held seventy patents, thirty-five related to the telephone. He invented stone pneumatic drills that were used in the building of the Library of Congress, a coin sorting machine, and a charcoal stamping machine. His Great Cumberland County Clock was an interesting electrical invention that could not keep accurate time because of variations in ground current.

Carlisle made national news when the McClintock Riot took place in 1847. Pennsylvania was a free state but three fugitive slaves were captured and brought to Carlisle on their way south – a girl named Ann, a man named Lloyd Brown, and a woman named Hester Norman, married to a free man, George Norman of Carlisle.

At the time, 300 freed men and women lived in Carlisle. The owners of the three fugitive slaves, Kennedy and Hollingsworth, were seeking certificates from a local justice to transport the fugitive slaves south, and permission to keep them in the county jail while they conducted other business.

A crowd gathered at the courthouse and a riot ensued. The judge had reluctantly decided that the escapees could not be jailed but that the certificates of ownership were valid. Kennedy was trampled and broke his knee in the melee; he died of his injuries three weeks later. Thirty-four black and white people and Professor McClintock were charged with inciting a riot. Thirteen people were convicted and eventually imprisoned for this riot.

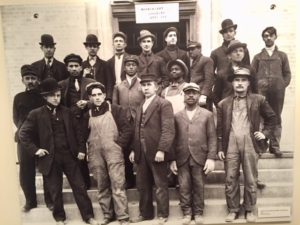

Iron furnaces existed in Cumberland County as self-sufficient plantation communities: farms, mills, workers’ homes, school, offices, church, cemetery, and a company store. The labor was composed of free laborers, indentured servants, some of whom were white, slaves, and apprentices. Women mended clothes, farmed, supplied wood, and finished iron casting. A 1800s ironworker made anywhere from 51 to 86 cents a day for 12 hours of work. Most people in this time period worked on farms or in farm-related fields such as milling, blacksmithing, and tanning.

Iron furnaces existed in Cumberland County as self-sufficient plantation communities: farms, mills, workers’ homes, school, offices, church, cemetery, and a company store. The labor was composed of free laborers, indentured servants, some of whom were white, slaves, and apprentices. Women mended clothes, farmed, supplied wood, and finished iron casting. A 1800s ironworker made anywhere from 51 to 86 cents a day for 12 hours of work. Most people in this time period worked on farms or in farm-related fields such as milling, blacksmithing, and tanning.

According to the museum archives, due in part to the tanning and iron industries, slavery lingered in Cumberland County even though it was abolished in Pennsylvania on March 1, 1780, one of the first states to do so. “In 1810, half of all the slaves held in Pennsylvania were in Cumberland County… Twenty-four Africans were still in bondage in 1840; 1847 was the first year that the county no longer held slaves.”

The museum archives explain that “Cumberland County was not a stronghold for abolitionists. Many residents had family and friends in slaveholding Maryland, southern born soldiers were in training at the Cavalry School at Carlisle Barracks, and nearly half of Dickinson’s students were from the south. Newspapers in the area were anti-abolitionist and slave catcher gangs roamed the county. After 1945, local churches forbade abolitionist meetings in their establishments.”

The new courthouse is located on the grounds of the former Market House Square. The Penn family, in their 1751 plan for Carlisle, had designated a portion of the square to be used as a market. Consequently, a market was held continuously on that spot from 1751 until 1952 when it was demolished to make way for the new courthouse, to the protests of many local conservationists.

The new courthouse is located on the grounds of the former Market House Square. The Penn family, in their 1751 plan for Carlisle, had designated a portion of the square to be used as a market. Consequently, a market was held continuously on that spot from 1751 until 1952 when it was demolished to make way for the new courthouse, to the protests of many local conservationists.

Twice a week markets were held here and overseen by the Clerk of the Market who used scales to validate the weight of the goods and produce sold. Three different buildings were erected to hold these markets, two open-air ones and one elaborate Victorian building.

On a quaint side street in the historical district, dotted with whimsically bright and colorful mom and pop stores, one particular shop displays in a large bay window numerous “progressive” signs of PEACE and COEXIST just in case you missed one.

On a quaint side street in the historical district, dotted with whimsically bright and colorful mom and pop stores, one particular shop displays in a large bay window numerous “progressive” signs of PEACE and COEXIST just in case you missed one.

Throughout downtown businesses posted flyers announcing its 15th annual food dinner on March 31 sponsored by the Dickinson College, celebrating local agriculture, with a keynote speaker, a fourth generation grocer with a conscience and a political message. She runs “an all-local grocery, deli, and craft beer bar that exists specifically to make climate change progress through responsible sourcing practices, resource-conscious equipment, power and packaging decisions, and the realization of a no-food-waste mandate. This market empowers shoppers to make incremental progress at a time when large-scale legislative change seems unlikely.”

The food will be delicious and expensive ($30) but the dinner sounds like a political drive in support of the debunked man-made climate change scheme rather than just an opportunity to sample locally grown and prepared food and to meet other like-minded progressive neighbors.

ILEANA JOHNSON

American By Choice