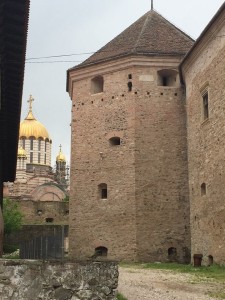

Prejmer Citadel Walls Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Prejmer Citadel Walls Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Leaving our hotel in Brasov and barely avoiding two collisions from impertinent drivers who seem to be in so much hurry that they triple and quadruple pass other vehicles close to dangerous curves and impassable hills, we made our way a few kilometers north to the neighboring Saxon villages of Prejmer and Harman.

According to National Geographic Traveler, the villagers who emigrated to German-speaking countries have abandoned their terra-cotta tile homes built very close to the road and gypsies have moved in (p. 146).

Harman’s Citadel has four turrets which indicated that “the people of Harman had the right to pass the death sentence.” The 12 meter tall walls were built in the 15th century to protect the citizens from the many outside invaders, eager for loot and tribute. A 12th century Gothic church with a 13th century funerary chapel are enclosed within the citadel rock walls. The chapel contains fragments of Gothic frescoes.

Prejmer citadel inner walls Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Prejmer citadel inner walls Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Prejmer’s Citadel walls, built between 15th and 18th centuries, protected inhabitants from constant siege coming from Austrians, Tatars, Turks, and other neighboring provinces. The inside walls had 272 rooms on four levels, refectories, a school, and galleries to accommodate the entire community during an attack. A circular passageway connected the top level. The middle courtyard was dominated by a Gothic place of worship built in the Rhineland church style. The Citadel had an exterior portal, a 17th century wall, the original 15the century defensive wall, and a 19th century wall extension and entrance passageway with a dropping gate with sharp wooden spikes that could impale someone unfortunate enough to be in the way when the gate dropped.

Prejmer residences Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Prejmer residences Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Pigeons, lilacs, and blossoming trees were shading the courtyard between the Gothic church and the sleeping quarters accessed by steep and dangerous wooden stairs, not for the faint of heart or wobbly jointed. I could not climb all the way to the top where the very thick rocky retaining walls and ramparts were slightly separated six feet from the residential part of the structure.

When the Citadel of Prejmer was under attack or times were dangerous, the local population took refuge inside the fortress. According to museum archives, an old school functioned here, with its first teachers mentioned in 1460 and then in 1556. The surviving classroom decorated with frescoes from the 18th century was used as late as 1853 when a new school was built in the village of Prejmer.

Prejmer drop gate Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Prejmer drop gate Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

One hundred-year old trees and purple lilacs bloomed in the courtyard, overwhelmed by the strong scent of mold and old, dry wood. The green grass made a lovely contrast with the dark and foreboding sleeping quarters now painted white, with black stained beams. Centuries ago, this citadel must have been an island of peace and protection from the constant Ottoman Empire attacks which continued for hundreds of years. Every time they were pushed back, they returned with a vengeance.

Ten miles from Brasov, after a pleasant drive through valleys flanked by blue mountains and lush green meadows with billowing in the wind tall grasses, wheat, and wild flowers, we found the city of Rasnov with its Citadel built by Teutonic knights in 1215. The fortress is perched on a rock about 400 feet above town. Because its location is difficult to access, the medieval castle was only conquered once in 1612 by Gabriel Bathory. The observation tower, which can be reached by steep, creaking, and difficult to climb up or down stairs, gives a breathtaking 360 degree view of the Carpathian Mountains. The movie Cold Mountain was filmed not far from here.

Cetatea Rasnov Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Cetatea Rasnov Photo: Ileana Johnson 2015

Archeological digs found evidence of a fortified Dacian settlement during the first century B.C. and first century A.D. named Cumidava/Comidava. Earthen moats, ditches dug around the rocky peaks, and wooden palisades protected the population from the numerous invasions. Parts of the fortification are still standing on the north side and in the surrounding forest. Houses, some carved in stone, were located inside the fortifications. Buried Items who were unearthed suggest a prosperous settlement with trade relations. When the Dacians were conquered by the Romans, a new Roman castrum was built on Ghimbasel Valley, bearing the same name, Cumidava/Comidava.

Three buses of American soldiers were visiting the fortress that day, climbing to the citadel on foot, while children and less physically-abled adults were ferried up by a tractor pulling a train of sorts. Humidity was low, the sun was shining, the temperature was a balmy 72, and the rocky remains of the former castle were buffeted by strong winds. A Romanian flag was proudly displayed on the highest peak of the castle.

A resident cat disappeared below a big drop through an open window, as if jumping to her death. We found her later at the entrance, safe and sound, eating a treat dropped by one of the American soldiers.

We have met several Americans the night before, dining in an outdoor pizzeria near the Black Church in Brasov. Some of these young men, part of the “show of force” exercise in Romania which ended in Brasov, were happy to be off and around so many beautiful young Romanian girls.

A couple of soldiers were now interviewed by a young Digi-24 crew about their stay in Brasov. Romanians at large were buzzing with fear in cafes and on the Internet that the Americans have come to occupy them, albeit it too late, one older man joked. “We could have used American help during WWII,” he said. We certainly did not need the Soviets, he added with sarcasm.

We bought two walking canes; besides an interesting display in the office, the canes were quite handy for climbing or steadying when walking on cobble stones or rocky terrain. And this fortress is difficult enough because it was dug into the Carpathian Mountains.

The Carpathian Mountains chain covers about one third of Romania and once formed Europe’s largest volcanic link. There is only one extinct crater left with its volcanic lake Sf. Ana north of Brasov. The U-shaped mountain chain runs from the northwest to the southwest of Romania.

The drive back took us through the Poiana Soarelui Street, a road winding up with constant hair pin curves and dizzying drops until we reached Poiana Brasov, a popular tourist destination in summer time for outdoor recreation and horseback riding, and a fabulous ski resort in wintertime.

ILEANA JOHNSON

American By Choice